Salah al-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, better known to the Western World as Saladin. I wanted to do an illustration of him because I’ve found him to be a very interesting historical figure. Coming from a Kurdish background, he became the first Sultan of Egypt and Syria in the 12th century, and is known best for his military campaigns against King Richard the Lionheart and the occupying Frankish crusader states. Over the centuries he became figure of admiration both to Muslims and Christians, with many stories, poems, and legends depicting him as a great leader and chivalric role model.

Most of the images of Saladin I’m familiar with are either the medieval fanarts that show him (ahistorically) jousting directly against Richard, very vintage illustrations, based on romantic stories like The Talisman by Sir Walter Scott that center around the adventures of crusaders, or clearly inspired by his portrayal by Ghassan Massoud in Ridley Scott’s 2005 film Kingdom of Heaven. Which is a very stunning and striking depiction, but one that like all historical films, has a specific focus.

I thought it would be a fun challenge to do an illustration based off artwork and depictions from the specific era.

Fatimid and Ayyubid Art

Saladin lived under the Fatimid caliph, al-Adid, in Egypt, before he came to power and established his own dynasty of the Ayyubids, named after his father, Ayyub, so I started off looking for artwork that would fall under the general time period of the latter half of the 12th century.

There aren’t very many portraits specifically of Saladin available of this time period, I remember in Middle School, my first exposure to learning a bit about art and history of the Islamic world, we were taught that most Islamic art was non-figurative—a vast oversimplication, not one I’m super qualified to analyze, but I do know there was quite a diversity of artistic tradition! There was definitively lots of thriving art during the 12th century, but when I first researched most of the writings I found were mostly to do with architecture rather than say, clothing. However I did find some works that were my direct inspirations.

First, there is this Ayyubid era dirham coin, which has the stamped name and titles of al-Nasir Salah al-Din, and shows a seated figure which we can presume is him. This is probably the most direct portrayal I have found.

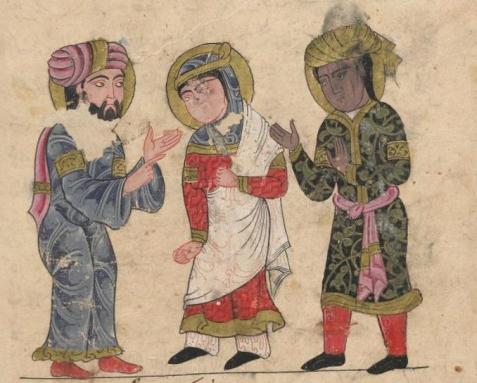

There is also this portrait, which comes up pretty easily in the Google search when one looks up “Saladin” and “Art.” According to World History Encyclopedia, it is listed as a portrait of Saladin by the artist Ismail al-Jazari.

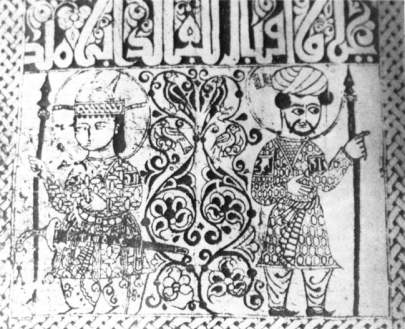

I also found some images of more everyday people around the fitting era. These aren’t very carefully sourced, as I found these reference images on this blog post, but I liked the look of them a lot. This is cheating somewhat, since I used Fatimid era artwork for my reference, but since Saladin lived and gained prominence under the Fatimids before rising to power, it still felt like it wouldn’t be too out of place.

Inspired by these images, I sketched out my idea, mostly working off the pose and design on the coin, however I also added designs and patterns inspired by the manuscript images and other sources.

Depending on which historian you read, one can have many takeaways from any particular figure. Saladin is a figure who is very “larger than life” in his legacy and culture, and this is reflected in his portrayals. However I wanted to do something that felt authoritative, but also a little more quieter and down to earth. After all, he is revered in legends and accounts not only as a warrior and leader, but for being generous, cultured, and chivalric. Historian John Gillingham, writing about some of the casual and political dealings between Saladin and Richard the Lionheart during the Third, attributes a sense of humor and slyness to his political dealings as well. So I thought it would be a fun aspect to include.

A Misattributed Portrait?

I originally was just going to write this blog post sharing my source images alongside the illustration that I did, and leave it at that. However, as I was pulling the sources to link them, something kept bothering me, especially about this picture.

I looked up the source for where the website got it’s image on Wikimedia commons, Which has the full page from which the image above comes from. On the full image, it says “Portrait of Saladin (?) Fatimid School, about A.D. 1180.” There are two sources listed for this image. One comes from an English art history book, The Miniature Painting and Painters of Persia, India and Turkey, published in 1912 by an F.R. Martin, who seems to be the one who decided that this might be Saladin, and put it in the caption mentioned above. The other source, possibly the source of the original folio that the work is a part of, is the Kitab fi ma’arifat al-hiyal al-handisaya, or The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, the famous work by artist, mathematician, and polymath Ismail al-Jazari.

However, the description about that book lists this figure as simply a figure sitting in front of a water clock, nothing about Saladin at all. I can’t read the original Arabic sadly, and can only do so much as far as sleuthing. It could be that it is intended to represent Saladin, but it could also just be some ordinary guy. I would need more information to find out, but seems like most sites that post this image just kind of go with the attribution by F.R. Martin that the figure is Saladin.

While I have not read all of Martin’s book, which is available on archive.org, I will say that it definitely approaches its subject in an extremely biased and dated way. The very first page of the book after the acknowledgement and table of contents opens with a paragraph claiming that the “Arabs of the ancient world” were a “simple race without great artistic feeling or interests” who relied on Christian artisans, and that while later caliphs desired more beauty in works, they were more busy “subduing and organizing their new dominions” than devoting time to art. I don’t pretend to be an expert on Arab or Islamic art, but at least I hope I have the decency to not make Wild Unsupported Statements like that in my own work. This is all to say, I have my doubts about the reliability of Mr. Martin’s theorizing that the above portrait is, indeed, Saladin, or is it one of those “Mask of Agamemnon” cases where one just lists the most recognizable figure one knows from the culture.

Conclusion

All in all, doing the portrait was a very fun and much needed exercise. I enjoyed doing the research a lot, and even in doing this write up I ended up learning a lot more by going down more rabbit holes about things like the works of Ismail al-Jazari, who wrote about a bunch of wild inventions such as this cool as hell elephant clock.

There may not be a “true” “historically accurate” portrait of Saladin the way we conceptualize it in the modern way, and of course my drawing is like all pieces of art before me, an interpretation based on my own connections and sensibilities. Like all historical figures, his legacy is one that is made up of actions and far reaching effects most of all, recorded by chroniclers and eyewitnesses, rather than just appearance. Everything else is interpretation and imagination through time.

I appreciate this in so many ways. Cool drawing!

LikeLike